31 KiB

% Haskell for Shell Scripting % Gabriel Gonzalez % April 8, 2015

Before class

If you haven't installed ghc, yet:

$ echo "/home/ggonzalez/tools/ghc-7.8.3-Darwin.x86_64" >> ~/.tools

$ sync-dottools.sh

... then open a new terminal window.

To test your Haskell installation, run these commands:

$ echo 'main = putStrLn "Hello, world!"' > hello.hs

$ runhaskell hello.hs

Hello, world!

Install the shell scripting library using these commands:

$ cabal update

$ cabal install turtle-1.1.0

Outline

- Haskell overview

- Subroutines

- Types

- Use

ghcias a shell - Type signatures

- String formatting

- Streams

- Pipes

- Folds

- Patterns

I've hosted slides on go/learn so that people can follow along locally

Overview of Haskell

Haskell is a purely functional language with strong and static types

-

Purely functional means side effect order is not tied to evaluation order

-

Strong types are fine-grained (i.e.

FilePath/Time/NamevsString) -

Static types catch errors at compile time

Haskell can be both interpreted or compiled to a native binary

Haskell is a managed language, providing garbage collection, concurrency, and transactional shared memory:

- Garbage collection is generational and efficient (measured in GB / s)

- Concurrency uses green-threads and is efficient (world record for SDN)

- Transactional memory simplifies race-free concurrent code without polling

Biggest disadvantages of Haskell

- Not a JVM language

- Beginners can't easily reason about performance

- Built-in record syntax is clumsy

- Most language features are libraries, which hampers discoverability

- Culture of abstraction astronauts (myself included)

Comparing Haskell to Scala

Similarities:

- Static types

- Strong types

- Functional

- Automatic memory management

Differences:

- Haskell is not object-oriented

- Haskell is not a JVM language

- Haskell has a faster startup time (10 ms compiled, < 1 second interpreted)

- Haskell compiles to native code

Comparing Haskell to Python

Similarities

- Lightweight syntax

- Significant whitespace (with optional curly braces)

- Procedural

- Automatic memory management

Differences:

- Haskell is statically typed (unless you enable

-fdefer-type-errors) - Haskell is strongly typed

- Haskell compiler/interpreter not pre-installed on most Unix-like systems

- Haskell compiles to native code

Why use Haskell for shell scripting?

Haskell has light-weight syntax and fast start-up times

Haskell code is easy to refactor and maintain

Hello, world!

Save this to: example.hs:

#!/usr/bin/env runhaskell

-- #!/bin/bash

{-# LANGUAGE OverloadedStrings #-} --

--

import Turtle --

--

main = echo "Hello, world!" -- echo Hello, world!

... then run the example:

$ chmod u+x example.hs

$ ./example.hs

Hello, world!

Create a native binary

$ ghc -O2 -threaded example.hs

$ ./example

Hello, world!

Use Haskell interactively

$ ghci -v0

Prelude> :set -XOverloadedStrings

Prelude> import Turtle

Prelude Turtle> echo "Hello, world!"

Hello, world!

Prelude Turtle> 2 + 2

4

Prelude Turtle> let f x = x + x

Prelude Turtle> f 2

4

Prelude Turtle> :quit

Load code into the REPL

$ ghci -v0 example.hs

*Main> main

Hello, world!

*Main> :quit

Exercise

What do you think this code does?

#!/usr/bin/env runhaskell

{-# LANGUAGE OverloadedStrings #-}

import Turtle

say = echo

main = say "Hello, world!"

Questions?

- Haskell overview

- Subroutines

- Types

- Use

ghcias a shell - Type signatures

- String formatting

- Streams

- Pipes

- Folds

- Patterns

Values

#!/usr/bin/env runhaskell

-- #!/bin/bash

{-# LANGUAGE OverloadedStrings #-} --

--

import Turtle --

--

str = "Hello, world!" -- STR='Hello, world!'

--

main = echo str -- echo $STR

$ ./example.hs

Hello, world!

str is immutable (analogous to Scala's val)

Why do you think Haskell defaults to immutability?

Order of definitions does not matter

#!/usr/bin/env runhaskell

{-# LANGUAGE OverloadedStrings #-}

import Turtle

main = echo str

str = "Hello, world!"

You need main

Modify your program to to eliminate main:

#!/usr/bin/env runhaskell

{-# LANGUAGE OverloadedStrings #-}

import Turtle

echo "Hello, world!"

You will get this error message if you run the program:

example.hs:7:1: Parse error: naked expression at top level

The top level of a Haskell program is declarative and only allows definitions

You cannot execute code at the top level

Subroutines

Use do to create a subroutine that runs more than one command:

Using significant whitespace:

#!/usr/bin/env runhaskell

-- #!/bin/bash

{-# LANGUAGE OverloadedStrings #-} --

--

import Turtle --

--

main = do --

echo "Line 1" -- echo Line 1

echo "Line 2" -- echo Line 2

$ ./example.hs

Line 1

Line 2

You can opt out of significant whitespace

main = do

{ echo "Line 1"

; echo "Line 2"

}

main = do {

echo "Line 1";

echo "Line 2";

}

main = do { echo "Line1"; echo "Line2" }

Storing results

#!/usr/bin/env runhaskell

-- #!/bin/bash

import Turtle --

--

main = do --

dir <- pwd -- DIR=$(pwd)

time <- datefile dir -- TIME=$(date -r $DIR)

print time -- echo $TIME

$ ./example.hs

2015-01-24 03:40:31 UTC

Why not this?

main = print(datetime(pwd))

Difference between (=) and (<-)

(<-)is overloaded; in this context it means "store the subroutine's result"(=)is not overloaded; equating two things means they are interchangeable

Example of overloading (<-):

Prelude> do { x <- [1, 2]; y <- [3, 4]; return (x, y) }

[(1,3),(1,4),(2,3),(2,4)]

do/(<-)/return is analogous to for/(<-)/yield in Scala:

scala> for { x <- Seq(1, 2); y <- Seq(3, 4) } yield (x, y)

res0: Seq[(Int, Int)] = List((1,3), (1,4), (2,3), (2,4))

Nesting subroutines

#!/usr/bin/env runhaskell

-- #!/bin/bash

import Turtle --

--

datePwd = do -- datePwd() {

dir <- pwd -- DIR=$(pwd)

result <- datefile dir -- RESULT=$(date -r $DIR)

return result -- echo $RESULT

-- }

main = do --

time <- datePwd -- TIME=$(datePwd)

print time -- echo $TIME

Same result:

$ ./example.hs

2015-01-24 03:40:31 UTC

Unnecessary return

You can simplify this:

datePwd = do -- datePwd() {

dir <- pwd -- DIR=$(pwd)

result <- datefile dir -- RESULT=$(date -r $DIR)

return result -- echo $RESULT

-- }

... to this:

datePwd = do -- datePwd() {

dir <- pwd -- DIR=$(pwd)

datefile dir -- date -r $DIR

-- }

The return value of a subroutine is the return value of its last command

return

return does not break from the surrounding subroutine

return is just a command whose return value is its argument

do x <- return expr -- X=EXPR

command x -- command $X

-- Same as:

do let x = expr -- X=EXPR

command x -- command $X

-- Same as:

command expr -- command EXPR

return is the only case where (<-) and (=) behave the same way

Single-command subroutines

main = do echo "Hello, world!"

-- Same as:

main = echo "Hello, world!"

do is only necessary if you want to chain multiple commands together

Exercise

What do you think this code does?

main = do

let x = print 1

print 2

Questions?

- Haskell overview

- Subroutines

- Types

- Use

ghcias a shell - Type signatures

- String formatting

- Streams

- Pipes

- Folds

- Patterns

Types

What happens if we use print instead of echo?

#!/usr/bin/env runhaskell

import Turtle

main = do

dir <- pwd

time <- datefile dir

echo time -- This used to be: print time

$ ./example.hs

example.hs:8:10:

Couldn't match expected type `Text' with actual type `UTCTime'

In the first argument of `echo', namely `time'

In a stmt of a 'do' block: echo time

In the expression:

do { dir <- pwd;

time <- datefile dir;

echo time }

Type-directed development - REPL

main = do

dir <- pwd

time <- datefile dir

echo time -- This used to be: print time

$ ghci -v0

Prelude> :set -XOverloadedStrings

Prelude> import Turtle

Prelude Turtle> :type pwd

pwd :: IO Turtle.FilePath

Prelude Turtle> :type datefile

datefile :: Turtle.FilePath -> IO UTCTime

Prelude Turtle> :type echo

echo :: Text -> IO ()

Prelude Turtle> :type print

print :: Show a => a -> IO ()

Type-directed development - Documentation

Visit:

https://hackage.haskell.org/package/turtle

repr

Use repr to render a human-readable representation of a value as Text:

-- This behaves like Python's `repr` function

repr :: Show a => a -> Text

print is (conceptually) the same as echo + repr:

print x = echo (repr x)

Basic types

IntDoubleText(a, b)[a]a -> bIO aFilePathExitCodeUTCTime

Exercise

What are the types of x, y, and z?

(Assume all string literals are Text and all numeric literals are Ints)

x = ("123", 4)

y = [2, 3]

z a = 1 + a

Answers

x :: (Text, Int)

x = ("123", 4)

y :: [Int]

y = [2, 3]

z :: Int -> Int

z a = 1 + a

Questions?

- Haskell overview

- Subroutines

- Types

- Use

ghcias a shell - Type signatures

- String formatting

- Streams

- Pipes

- Folds

- Patterns

Customize ghci

Create a .ghci file in your current directory that looks like this:

:set -XOverloadedStrings

import Turtle

This automatically runs the above two commands every time you run ghci

ghci searches the current directory and your home directory for a .ghci file

Use ghci like a shell

$ ghci -v0

Prelude Turtle> view (ls ".")

FilePath "/Users/ggonzalez/.bash_history"

FilePath "/Users/ggonzalez/.bash_profile"

FilePath "/Users/ggonzalez/.bashrc"

...

FilePath "/Users/ggonzalez/workspace"

Prelude Turtle> cd "/tmp"

Prelude Turtle> pwd

FilePath "/private/tmp"

Prelude Turtle> touch "foo.txt"

Prelude Turtle> testfile "foo.txt"

True

Prelude Turtle> rm "foo.txt"

Prelude Turtle> testfile "foo.txt"

False

Prelude Turtle> test<TAB>

testdir testfile

Prelude Turtle> testdir "/tmp/<TAB>

.vbox-ggonzalez-ipc

KSOutOfProcessFetcher.0.r55jifrBu08ZlGAfPLYXKgYad4c=

launch-0kuyez

...

sync-dottools.stdout.log

ghci auto-print

ghci implicitly prints any value that is not a subroutine

Prelude Turtle> 2 + 2

4

Prelude Turtle> "123" <> "456" -- (<>) concatenates strings

"123456"

The behavior is the same as if we had explicitly called print:

Prelude Turtle> print (2 + 2)

4

Prelude Turtle> print ("123" <> "456")

"123456"

Shell commands

Prelude Turtle> shell "true" empty

ExitSuccess

Prelude Turtle> shell "false" empty

ExitFailure 1

Prelude Turtle> shell "ls | wc -l" empty

5

ExitSuccess

Use proc if you want safer command templating:

Prelude Turtle> -- ls /tmp /usr

Prelude Turtle> proc "ls" ["/tmp", "/usr"] empty

/tmp:

KSOutOfProcessFetcher.0.r55jifrBu08ZlGAfPLYXKgYad4c=

...

/usr:

X11 bin lib local share

X11R6 include libexec sbin standalone

ExitSuccess

Exercise

Within ghci:

- Create a directory named

dir1 - Rename

dir1todir2 - Delete

dir2

Answers

Prelude Turtle> mkdir "dir1"

Prelude Turtle> mv "dir1" "dir2"

Prelude Turtle> rmdir "dir2"

Questions?

- Haskell overview

- Subroutines

- Types

- Use

ghcias a shell - Type signatures

- String formatting

- Streams

- Pipes

- Folds

- Patterns

Type signatures

#!/usr/bin/env runhaskell

import Turtle

-- +----- A subroutine ...

-- |

-- | +-- ... that returns `UTCTime`

-- | |

-- v v

datePwd :: IO UTCTime

datePwd = do

dir <- pwd

datefile dir

-- +----- A subroutine ...

-- |

-- | +-- ... that returns an empty value (i.e. `()`)

-- | |

-- v v

main :: IO ()

main = do

time <- datePwd

print time

Machine-checked documentation

str :: Int -- Oops!

str = "Hello!"

main :: IO ()

main = echo str

$ ./example.hs

example.hs:8:7:

No instance for (IsString Int)

arising from the literal `"Hello, world!"'

Possible fix: add an instance declaration for (IsString Int)

In the expression: "Hello, world!"

In an equation for `str': str = "Hello, world!"

example.hs:11:13:

Couldn't match expected type `Text' with actual type `Int'

In the first argument of `echo', namely `str'

In the expression: echo str

In an equation for `main': main = echo str

OverloadedStrings

Anything that implements IsString can be represented by a string literal

Examples we've seen so far:

FilePathText- ???

Reverse the error

str :: Text

str = 4

main :: IO ()

main = echo str

$ ./example.hs

example.hs:8:7:

No instance for (Num Text)

arising from the literal `4'

Possible fix: add an instance declaration for (Num Text)

In the expression: 4

In an equation for `str': str = 4

Num

Anything that implements Num can be represented by a numeric literal

Examples we've seen so far:

IntDouble- ???

Types clarify documentation

shell

:: Text -- Command line

-> Shell Text -- Standard input (as lines of `Text`)

-> IO ExitCode -- Exit code of the shell command

proc

:: Text -- Program

-> [Text] -- Arguments

-> Shell Text -- Standard input (as lines of `Text`)

-> IO ExitCode -- Exit code of the shell command

Type inference

Haskell (almost always) does not require type annotations

Type signatures are for the benefit of the programmer, not the compiler

Example:

Prelude Turtle> let addAsText x y = repr (x + y)

Prelude Turtle> :type addAsText

addAsText :: (Show a, Num a) => a -> a -> Text

Prelude Turtle> addAsText 2 3

"5"

No need to annotate argument types

No need to specify interfaces

No need to specify generic type parameters

Exercise

Use the compiler to infer the type of this function:

swap (x, y) = (y, x)

Answer

Prelude Turtle> :type swap

swap :: (t1, t) -> (t, t1)

Questions?

- Haskell overview

- Subroutines

- Types

- Use

ghcias a shell - Type signatures

- String formatting

- Streams

- Pipes

- Folds

- Patterns

Exit codes

#!/usr/bin/env runhaskell

{-# LANGUAGE OverloadedStrings #-}

import Turtle

main = do

let cmd = "false"

x <- shell cmd empty

case x of

ExitSuccess -> return ()

ExitFailure n -> die (cmd <> " failed with exit code: " <> repr n)

This always prints an error message since false always fails:

$ ./example.hs

example.hs: user error (false failed with exit code: 1)

String formatting

We can replace this:

cmd <> " failed with exit code: " <> repr n

... with printf-style formatting:

format (s%" failed with exit code: "%d) cmd n

The compiler infers the number and types of arguments from the format string:

Prelude Turtle> :type format (s%" failed with exit code: "%d)

format (s%" failed with exit code: "%d) :: Text -> Int -> Text

Exercise

What do you think these print out?

Prelude Turtle> format ("A "%s%" string that takes "%d%" arguments") "format" 2

Prelude Turtle> format "I take 0 arguments"

The Format type

A format string is not Text!

Prelude Turtle> :type format

format :: Format Text r -> r

So what is going on here?

Prelude Turtle> format "I take 0 arguments"

Format implements IsString

(%) :: Format b c -> Format a b -> Format a c

"A " :: Format a a

s :: Format a (String -> a)

" string that takes " :: Format a a

d :: Format a (Int -> a)

" arguments" :: Format a a

"A "%s%" string that takes "%d%" arguments" :: Format a (Text -> Int -> a)

format "A "%s%" string that takes "%d%" arguments" :: Text -> Int -> Text

You can build your own format specifiers!

OverloadedStrings

Examples we've seen so far:

FilePathTextFormat- ???

Questions?

- Haskell overview

- Subroutines

- Types

- Use

ghcias a shell - Type signatures

- String formatting

- Streams

- Pipes

- Folds

- Patterns

Streams

You've already encountered at least one stream: the ls command

Prelude Turtle> :type ls

ls :: Turtle.FilePath -> Shell Turtle.FilePath

A "Shell a" is a stream of "a"s

Streams are not subroutines, so you can't run them directly within ghci:

Prelude Turtle> ls "/tmp"

<interactive>:2:1:

No instance for (Show (Shell Turtle.FilePath))

arising from a use of `print'

Possible fix:

add an instance declaration for (Show (Shell Turtle.FilePath))

In a stmt of an interactive GHCi command: print it

ghci tries to print the Shell stream, but fails because Shell does not

implement Show

view

The view command is the simplest way to display a Shell stream:

view :: Show a => Shell a -> IO ()

view prints every element of the stream:

Prelude Turtle> view (ls "/tmp")

FilePath "/tmp/.X11-unix"

FilePath "/tmp/.X0-lock"

FilePath "/tmp/pulse-PKdhtXMmr18n"

FilePath "/tmp/pulse-xHYcZ3zmN3Fv"

FilePath "/tmp/tracker-gabriel"

FilePath "/tmp/pulse-PYi1hSlWgNj2"

FilePath "/tmp/orbit-gabriel"

FilePath "/tmp/ssh-vREYGbWGpiCa"

FilePath "/tmp/.ICE-unix

The empty stream

empty :: Shell a

The empty stream emits nothing:

Prelude Turtle> view empty -- Outputs nothing

Prelude Turtle>

In other words:

view empty = return ()

The singleton stream

return :: a -> Shell a

return builds a singleton stream that emits exactly one element:

1 :: Int

return 1 :: Shell Int

Prelude Turtle> view (return 1)

1

In other words:

view (return x) = print x

Embedding subroutines

liftIO :: IO a -> Shell a

liftIO transforms a subroutine into a singleton stream:

pwd :: IO Turtle.FilePath

liftIO pwd :: Shell Turtle.FilePath

Prelude Turtle> view (liftIO pwd)

FilePath "/tmp"

In other words:

view (liftIO io) = do x <- io

print x

Concatenate streams

(<|>) :: Shell a -> Shell a -> Shell a

(<|>) concatenates two streams together to build a new stream:

Prelude Turtle> view (return 1 <|> return 2)

1

2

In other words:

view (xs <|> ys) = do view xs

view ys

A more complex Shell stream

Prelude Turtle> view (ls "/tmp" <|> liftIO home <|> ls "/usr" <|> return "/lib")

FilePath "/tmp/.X11-unix"

FilePath "/tmp/.X0-lock"

FilePath "/tmp/pulse-PKdhtXMmr18n"

FilePath "/tmp/pulse-xHYcZ3zmN3Fv"

FilePath "/tmp/tracker-gabriel"

FilePath "/tmp/pulse-PYi1hSlWgNj2"

FilePath "/tmp/orbit-gabriel"

FilePath "/tmp/ssh-vREYGbWGpiCa"

FilePath "/tmp/.ICE-unix"

FilePath "/Users/ggonzalez"

FilePath "/usr/lib"

FilePath "/usr/src"

FilePath "/usr/sbin"

FilePath "/usr/include"

FilePath "/usr/share"

FilePath "/usr/games"

FilePath "/usr/local"

FilePath "/usr/bin"

FilePath "/lib"

Reasoning about streams

view (ls "/tmp" <|> liftIO home <|> ls "/usr" <|> return "/lib")

... is the same as:

do view (ls "/tmp")

dir <- home

print dir

view (ls "/usr")

print "/lib"

Shell implements IsString

Prelude Turtle> view "123"

"123"

Prelude Turtle> view (return "123") -- Same thing

"123"

Prelude Turtle> view ("123" <|> "456")

"123"

"456"

Prelude Turtle> view (return "123" <|> return "456") -- Same thing

"123"

"456"

OverloadedStrings

Examples seen so far:

FilePathTextFormatShell- ???

select

You can build a Shell stream from a list:

select :: [a] -> Shell a

Example:

Prelude Turtle> view (select [1, 2, 3])

1

2

3

Loops

We can use select to loop within a Shell:

#!/usr/bin/env runhaskell

-- #!/bin/bash

{-# LANGUAGE OverloadedStrings #-} --

--

import Turtle --

--

example :: Shell () --

example = do --

x <- select [1, 2] -- for x in 1 2; do

y <- select [3, 4] -- for y in 3 4; do

liftIO (print (x, y)) -- echo \(${x},${y}\);

-- done;

main = sh example -- done

This prints every permutation of x and y:

$ ./example

(1,3)

(1,4)

(2,3)

(2,4)

The sh utility

sh is like view, except that it doesn't print any elements:

view :: Show a => Shell a -> IO ()

sh :: Shell a -> IO ()

Looping over arbitrary Shells

You can loop over things other than select:

Prelude Turtle> -- for file in /tmp/*; do echo $file; done

Prelude Turtle> sh (do file <- ls "/tmp"; liftIO (print file))

FilePath "/tmp/.X11-unix"

FilePath "/tmp/.X0-lock"

FilePath "/tmp/pulse-PKdhtXMmr18n"

FilePath "/tmp/pulse-xHYcZ3zmN3Fv"

FilePath "/tmp/tracker-gabriel"

FilePath "/tmp/pulse-PYi1hSlWgNj2"

FilePath "/tmp/orbit-gabriel"

FilePath "/tmp/ssh-vREYGbWGpiCa"

FilePath "/tmp/.ICE-unix"

In fact, that is how view is implemented:

view :: Show a => Shell a -> IO ()

view s = sh (do { x <- s; liftIO (print x) })

Questions?

- Haskell overview

- Subroutines

- Types

- Use

ghcias a shell - Type signatures

- String formatting

- Streams

- Pipes

- Folds

- Patterns

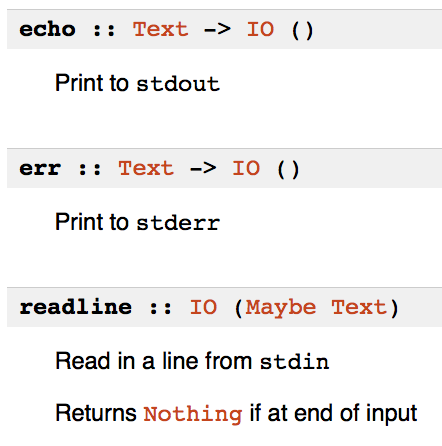

stdout

stdout :: Shell Text -> IO ()

stdout s = sh (do

txt <- s

liftIO (echo txt) )

Standard out writes each Text element of the stream to a separate line:

Prelude Turtle> stdout "Line 1"

Line 1

Prelude Turtle> stdout ("Line 1" <|> "Line 2")

Line 1

Line 2

stdin

stdin :: Shell Text

stdin streams lines from standard input:

#!/usr/bin/env runhaskell

-- #!/bin/bash

{-# LANGUAGE OverloadedStrings #-} --

--

import Turtle --

--

main = stdout stdin -- cat

stdin keeps producing lines until hitting EOF:

$ ./example.hs

ABC<Enter>

ABC

Test<Enter>

Test

42<Enter>

42

<Ctrl-D>

(&)

If you prefer to read left-to-right, you can use the infix (&) operator:

(&) :: a -> (a -> b) -> b

x & f = f x

main = stdin & stdout

input and output

input :: FilePath -> Shell Text

output :: FilePath -> Shell Text -> IO ()

Run these examples:

Prelude Turtle> output "file.txt" ("Test" <|> "ABC" <|> "42")

Prelude Turtle> stdout (input "file.txt")

Test

ABC

42

Or left-to-right:

Prelude Turtle> "Test" <|> "ABC" <|> "42" & output "file.txt"

Prelude Turtle> input "file.txt" & stdout

Test

ABC

42

inshell

inshell

:: Text -- Command line

-> Shell Text -- Standard input to feed to program

-> Shell Text -- Standard output produced by program

Prelude Turtle> output "ls.txt" (inshell "ls" empty)

Prelude Turtle> stdout (input "ls.txt")

.X11-unix

.X0-lock

...

.ICE-unix

Turtle Prelude> output "awk.txt" (inshell "awk '{ print $1 }'" "123 456")

Turtle Prelude> stdout (input "awk.txt")

123

inshell (Left-to-right)

Turtle Prelude> "123 456" & inshell "awk '{ print $1 }'" & output "awk.txt"

Turtle Prelude> input "awk.txt" & stdout

123

inproc

inproc

:: Text -- Program

-> [Text] -- Arguments

-> Shell Text -- Standard input to feed to program

-> Shell Text -- Standard output produced by program

Turtle Prelude> stdout (inproc "awk" ["{ print $1 }"] "123 456")

123

Exercise

Build the following pipeline within the REPL:

- Use

inputto read inexample.hs - Use

inshell/inprocto number the lines with the Unixnlutility - Use

outputto write the result tonumbered.txt

The result should be equivalent to this Unix command:

$ nl < example.hs > numbered.txt

Answer

Prelude Turtle> input "example.hs" & inproc "nl" [] & output "numbered.txt"

Questions?

- Haskell overview

- Subroutines

- Types

- Use

ghcias a shell - Type signatures

- String formatting

- Streams

- Pipes

- Folds

- Patterns

Folds

Use a Fold to reduce the stream to a single value:

Prelude Turtle> import qualified Control.Foldl as Fold

Prelude Turtle Fold> fold (ls "/tmp") Fold.length

9

Prelude Turtle Fold> fold (ls "/tmp") Fold.head

Just (FilePath "/tmp/.X11-unix")

You can combine folds:

Prelude Turtle Fold> let minMax = (,) <$> Fold.minimum <*> Fold.maximum

Prelude Turtle Fold> fold (select [1..10]) minMax

(Just 1,Just 10)

Exercise

What are the types of:

foldFold.lengthFold.head

Answer

fold :: Shell a -> Fold a b -> IO b

Fold.length :: Fold a Int

Fold.head :: Fold a (Maybe a)

ls :: Shell Turtle.FilePath

fold :: Shell a -> Fold a b -> IO b

fold (ls "/tmp") :: Fold Turtle.FilePath b -> IO b

fold (ls "/tmp") Fold.length :: IO Int

Fold implements Num

>>> fold (select [1..10]) Fold.sum

55

>>> fold (select [1..10]) (1 + 2 * Fold.sum)

111

>>> fold (select [1..10]) (Fold.length + Fold.sum)

65

>>> fold (select [1..10]) 5

5

Examples so far:

- Int

- Double

- Fold

Questions?

- Haskell overview

- Subroutines

- Types

- Use

ghcias a shell - Type signatures

- String formatting

- Streams

- Pipes

- Folds

- Patterns

Patterns

You can transform streams using Unix-like utilities, like grep:

Prelude Turtle> stdout (input "file.txt")

Test

ABC

42

Prelude Turtle> stdout (grep "ABC" (input "file.txt"))

ABC

However, the first argument of grep is not a string!

grep :: Pattern a -> Shell Text -> Shell Text

grep matches against a Pattern, which implements IsString

Comparison to regular expressions

Here is how to translate regular expression idioms to patterns:

Regex Pattern

========= =========

"string" "string"

. dot

e1 e2 e1 <> e2

e1 | e2 e1 <|> e2

e* star e

e+ plus e

e*? selfless (star e)

e+? selfless (plus e)

e{n} count n e

e? option e

[xyz] oneOf "xyz"

[^xyz] noneOf "xyz"

Pattern examples

Prelude Turtle> -- grep '^[[:digit:]]\+$' file.txt

Prelude Turtle> stdout (grep (plus digit) (input "file.txt"))

42

Prelude Turtle> -- grep '^[[:digit:]]\+\|Test$' file.txt

Prelude Turtle> stdout (grep (plus digit <|> "Test") (input "file.txt"))

Test

42

Patterns match the entire string by default

To match the interior of the string, use has:

Prelude Turtle> -- grep B file.txt

Prelude Turtle> stdout (grep (has "B") (input "file.txt"))

ABC

prefix and suffix match the beginning or end of a string, respectively:

Prelude Turtle> -- grep '^A' file.txt

Prelude Turtle> stdout (grep (prefix "A") (input "file.txt"))

ABC

Prelude Turtle> -- grep 'C$' file.txt

Prelude Turtle> stdout (grep (suffix "C") (input "file.txt"))

ABC

match

match :: Pattern a -> Text -> [a]

Prelude Turtle> match ("can" <|> "cat") "cat"

["cat"]

Prelude Turtle> match ("can" <|> "cat") "dog"

[]

Prelude Turtle> match (decimal `sepBy` ",") "1,2,3"

[[1,2,3]]

Prelude Turtle> match (prefix (decimal `sepBy` ",")) "1,2,3"

[[1,2,3],[1,2],[1],[]]

Patterns can do more than regular expressions

bit :: Pattern Bool

bit = (do { "0"; return False }) <|> (do { "1"; return True })

portableBitMap :: Pattern [[Bool]]

portableBitMap = do

"P1"

spaces1

width <- decimal

spaces1

height <- decimal

count width (count height (do { spaces1; bit }))

Prelude Turtle> match (prefix portableBitMap) "P1\n2 2\n0 0\n1 0\n"

[[[False,False],[True,False]]]

P1

2 2

0 0

1 0

Real parsing example

{-# LANGUAGE OverloadedStrings #-}

import Turtle

import Data.Time

entry :: Text

entry = "2015-03-27 10:25:40+0000 [-] 10.45.209.121 ..."

pattern = do

year <- decimal

"-"

month <- decimal

"-"

day <- decimal

" "

hour <- decimal

":"

minute <- decimal

":"

second <- decimal

let d = fromGregorian year month day

let t = TimeOfDay hour minute second

return (d, t)

Patterns are typed

$ ghci -v0 pattern.hs

*Main Turtle> :type pattern

pattern :: Pattern (Day, TimeOfDay)

*Main Turtle> match (prefix pattern) entry

[(2015-03-27,10:25:40),(2015-03-27,10:25:04)]

Exercise

Create a pattern that parses two integers stored in a string representation of a tuple:

tuple :: Pattern (Int, Int)

tuple = ???

Such that you get this result when you use it:

>>> match tuple "(3,4)"

[(3,4)]

Answer

tuple :: Pattern (Int, Int)

tuple = do

"("

x <- decimal

","

y <- decimal

")"

return (x, y)

Questions?

Conclusions

You can use Haskell as a "better Bash", getting types for free without slow startup times or heavyweight syntax.

If you want others to run your Haskell scripts, they can use dottools to install

ghc on their machine.

I also have a relocatable ghc uploaded to Packer that you can use to interpret

scripts on Mesos.

We also have an internal Hackage server at Twitter (go/hackage)

Visit https://hackage.haskell.org/package/turtle for more extensive documentation on the shell scripting library we used today